When you prescribe a generic medication, you’re not just choosing a cheaper option-you’re stepping into a legal gray zone that could put your license, reputation, and finances at risk. It’s not about being careless. It’s about how the law has changed, and how little most doctors realize they’re now on the front line when something goes wrong.

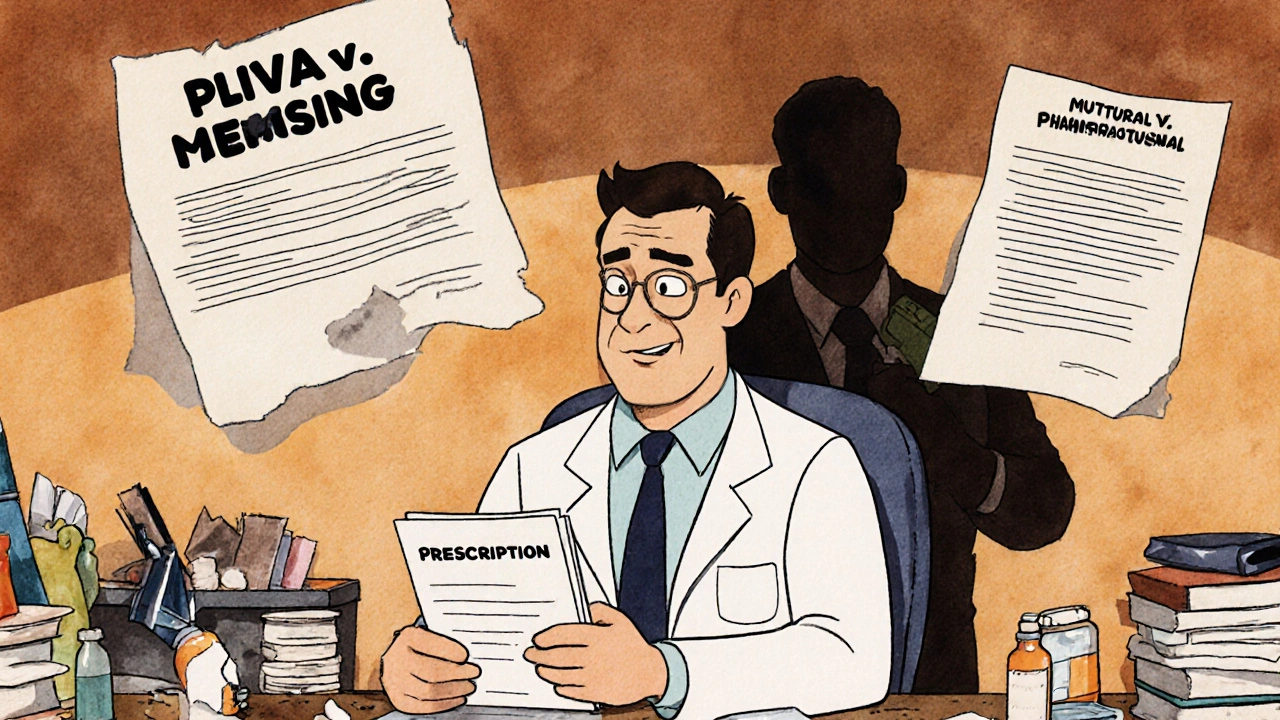

The Law Changed, But Many Doctors Didn’t Notice

In 2011 and 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court made two rulings-PLIVA v. Mensing and Mutual Pharmaceutical v. Bartlett-that quietly shifted the entire liability landscape for generic drugs. These decisions said generic manufacturers can’t be sued for failing to update warning labels, even if a drug causes serious harm. Why? Because federal law forces them to copy the brand-name label exactly. They can’t change it on their own. That sounds like a win for drug companies. But for doctors? It’s a trap. When a patient is injured by a generic drug, the manufacturer is legally shielded. The pharmacy that dispensed it? Usually protected too. That leaves one person standing in the legal crosshairs: the prescribing physician. A 2020 report from the American Bar Association found a 37% spike in lawsuits targeting doctors over generic drug injuries between 2014 and 2019. Patients aren’t suing manufacturers anymore. They’re suing you.What Makes a Doctor Liable?

To win a malpractice case, a patient’s lawyer only needs to prove three things:- You had a duty to the patient (you were their doctor).

- You broke that duty (you didn’t meet the standard of care).

- Your action-or inaction-directly caused the harm.

State Laws Are a Patchwork-And You’re the One Who Has to Navigate Them

Forty-nine states allow pharmacists to swap brand-name drugs for generics unless you write “dispense as written” on the prescription. But here’s where it gets messy:- In 32 states, the pharmacist must notify you within 72 hours if they substitute.

- In 17 states? No notification required at all.

High-Risk Drugs Are the Biggest Danger

Not all generics are equal. Some drugs have a narrow therapeutic index-meaning even a tiny change in dosage or formulation can cause serious harm. These include:- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Levothyroxine (thyroid hormone)

- Phenytoin and carbamazepine (anti-seizure meds)

- Lithium (mood stabilizer)

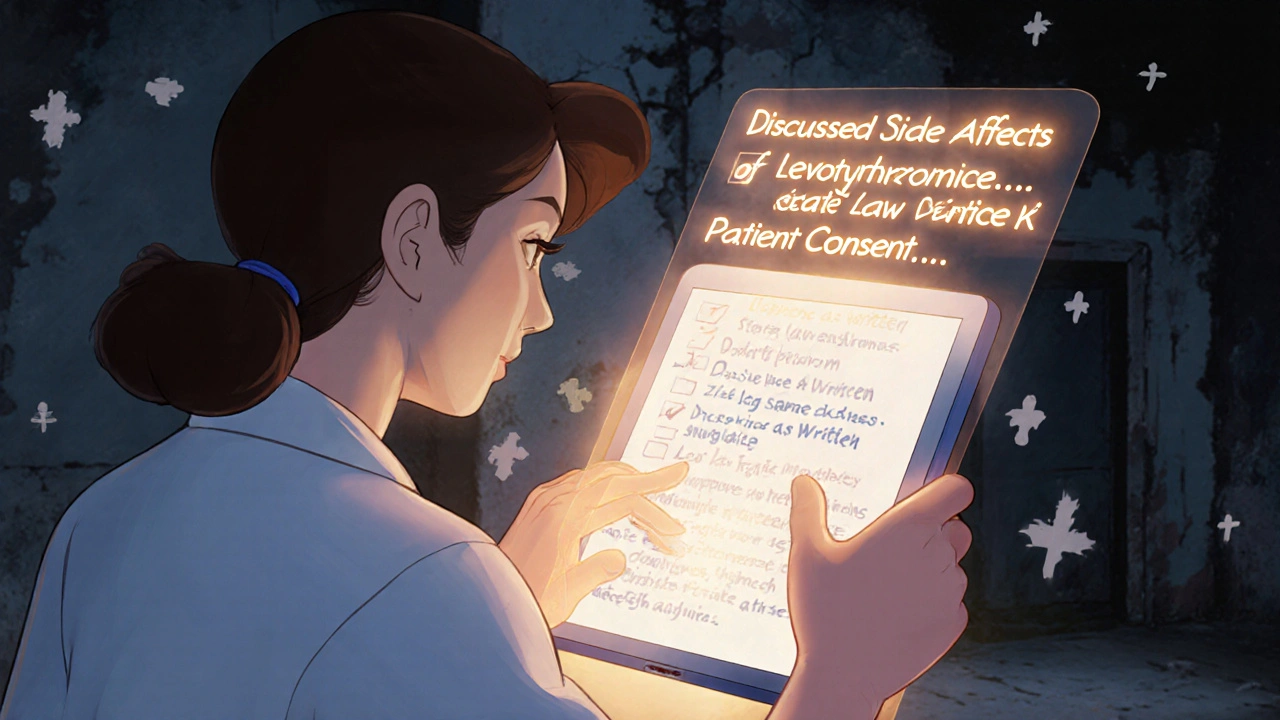

Documentation Is Your Best Legal Shield

The difference between a lawsuit and no lawsuit often comes down to one thing: your notes. A 2023 report from Medical Risk Management, Inc. found that doctors who documented specific conversations about generic substitution reduced their liability exposure by 58%. Generic notes like “medication discussed” won’t cut it. You need details. Here’s what works:“I discussed potential side effects of [medication], including [specific side effects], and advised you to avoid [specific activity] while taking this drug. I explained that a generic version may be dispensed, and that while it’s chemically equivalent, minor differences in formulation can affect how your body responds.”Electronic health records now have mandatory fields for this. Epic Systems added them in 2021. If your system doesn’t prompt you to document this, you’re falling behind. And don’t forget: your malpractice insurer knows this. The American Professional Agency reports a 7.3% premium surcharge for physicians who prescribe generics without documented counseling. That’s not a small fee. It’s a warning.

Doctors Are Changing How They Prescribe-Because They Have To

A 2022 AMA survey of 1,200 physicians found that 68% feel more anxious about prescribing generics. Forty-two percent admit they sometimes choose brand-name drugs just to avoid liability-even when it costs the patient more. On physician forums like Sermo, doctors share stories like this: “I prescribed a generic antiepileptic. Patient had a seizure. Manufacturer can’t be sued. Now I’m being sued. I followed every guideline. But the jury didn’t care.” The American College of Physicians documented 47 malpractice claims tied to generic drugs between 2016 and 2021. Twelve resulted in settlements averaging $327,500. You’re not alone. But you’re also not protected by tradition anymore.The Bigger Picture: Why This Is Getting Worse

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. That number has jumped from 62% in 2005. More prescriptions. Fewer manufacturers liable. More lawsuits against doctors. Congress has considered bills like H.R. 958 to restore some liability to manufacturers. None have passed. The pharmaceutical industry has spent over $14 million lobbying against changes that would increase their legal exposure. Meanwhile, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals made a small crack in the wall in 2023 with Johnson v. Teva Pharmaceuticals. It ruled that if a brand-name manufacturer updates its warning label, and the generic maker ignores it, the generic company can be sued. But this only applies in rare cases-and only in some federal circuits. For now, the rule remains: you are the last line of defense.What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to stop prescribing generics. But you need to change how you do it.- Use “dispense as written” for high-risk drugs-every time.

- Document specific counseling in your EHR. Don’t just check a box. Write what you said.

- Know your state’s substitution laws. If your state doesn’t require pharmacist notification, assume you won’t be told.

- Ask patients if they’ve switched generics before. Did they have side effects? Did their doctor warn them?

- Review your malpractice policy. Does it cover generic-related claims? Ask your insurer.

Can I be sued if I prescribe a generic drug and the patient has a bad reaction?

Yes. Since the 2011 and 2013 Supreme Court rulings, generic drug manufacturers are generally immune from liability for failure-to-warn claims. If a patient is harmed, they’re more likely to sue the prescribing physician, especially if there’s no documentation that you discussed risks or advised against substitution.

Do I need to write “dispense as written” on every prescription?

No-but you should for high-risk medications like warfarin, levothyroxine, and anti-seizure drugs. These have narrow therapeutic windows, and even small differences in generic formulations can cause serious harm. In 32 states, writing this phrase blocks substitution. Even in states where it doesn’t, it strengthens your legal position.

Is it legal to prescribe a brand-name drug just to avoid liability?

Yes, as long as it’s medically appropriate. Many physicians do this to reduce legal risk, especially with drugs where generic switching has caused documented harm. While this increases patient costs, courts have generally upheld a doctor’s right to choose based on safety concerns, not just cost.

What should I document when prescribing generics?

Don’t just write “medication discussed.” Instead, document: the specific drug, known side effects, advice given (e.g., “avoid driving”), and that you explained the possibility of generic substitution. Example: “Discussed side effects of levothyroxine including palpitations and anxiety. Advised patient to report any new symptoms. Explained that pharmacy may dispense generic version; while chemically equivalent, minor formulation differences may affect absorption.”

Are generic drugs less safe than brand-name drugs?

Generally, no. Generic drugs are required by the FDA to be bioequivalent to their brand-name counterparts. But bioequivalence doesn’t mean identical in every way-especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic indices. Small differences in fillers, coatings, or release mechanisms can affect absorption, leading to adverse effects in sensitive patients. The risk isn’t about quality-it’s about variability and lack of warning.

Iska Ede

November 18, 2025

Oh wow, so now we’re the designated fall guys for Big Pharma’s legal loopholes? 🙃 Guess I’ll just start charging patients $500 just to sign a waiver saying I warned them not to breathe while taking levothyroxine. At this point, I’m not a doctor-I’m a liability liability.

Kristi Joy

November 18, 2025

I get it-this is terrifying. But you’re not alone. I started using the exact documentation template from the AMA’s guidelines last year, and honestly? It’s been a game-changer. I don’t just check boxes anymore-I write real sentences. ‘Discussed potential fatigue with levothyroxine, advised not to drive if dizzy, noted generic substitution possible.’ Simple. Clear. Legally sound. You’ve got this.

Hal Nicholas

November 19, 2025

Let’s be real-this is what happens when you let bureaucrats write laws and then expect doctors to be clairvoyant. You’re supposed to memorize 49 different state laws, guess which generics are ‘safe enough,’ and still document every single word you said to a patient who’s half-asleep on a Tuesday at 4 PM? This isn’t medicine. It’s legal Russian roulette.

Louie Amour

November 20, 2025

Wow. Just… wow. You’re telling me you’re actually surprised by this? You think the FDA, the courts, and Big Pharma gave a single damn about your liability? They’ve been outsourcing risk to you since the 90s. If you didn’t know this was coming, you weren’t paying attention-you were just billing and smiling. This isn’t a crisis. It’s a consequence.

Christine Eslinger

November 20, 2025

There’s a quiet revolution happening in primary care right now-not because of new tech, but because of documentation. I used to write ‘meds discussed.’ Now I write: ‘Explained that generic carbamazepine may have different fillers; advised to monitor for dizziness or rash; confirmed patient understood substitution risk.’ It takes 45 extra seconds. But in court? That’s your armor. And yes, your insurer will notice. And yes, it’s worth every second. You’re not just documenting-you’re protecting.

Denny Sucipto

November 22, 2025

I’ve been there. Prescribed a generic for a patient with epilepsy. They had a seizure. I felt like I failed. Turns out the pharmacy switched it without telling me, and I never documented the warning. After that, I started printing out a one-pager for every high-risk med-side effects, substitution risk, what to watch for-and I hand it to the patient. They appreciate it. And honestly? So do I. It’s not just legal. It’s human.

Holly Powell

November 24, 2025

The entire liability framework is a product of federal preemption doctrine, which, in conjunction with the Hatch-Waxman Act, created a regulatory vacuum where prescribers became the de facto risk-bearing agents of pharmaceutical market dynamics. The absence of label autonomy for ANDA holders effectively externalizes tort liability to the prescribing physician, whose clinical discretion is now the sole locus of warning responsibility-a legal asymmetry that is both structurally perverse and ethically untenable.

Emanuel Jalba

November 24, 2025

THIS IS WHY WE CAN’T HAVE NICE THINGS 😭💔 I just lost a patient to a generic blood thinner. The manufacturer? Immune. The pharmacist? Didn’t tell me. I wrote ‘meds discussed.’ That’s it. Now I’m getting a letter from my malpractice insurer. I’m crying in my car after rounds. Please tell me I’m not the only one?

Heidi R

November 26, 2025

You’re all overreacting. Just don’t prescribe generics. Problem solved.

Brenda Kuter

November 26, 2025

They’re watching us. The insurance companies, the pharma lobbyists-they’re tracking who writes ‘dispense as written’ and who doesn’t. This isn’t about law. It’s about control. They want you scared. They want you prescribing only brand names so they can jack up prices. I saw a memo. It’s all planned. I’m not paranoid. I’m informed.

Shaun Barratt

November 27, 2025

While the legal and regulatory landscape pertaining to generic pharmaceutical liability has undergone significant transformation in the past decade, the onus of clinical documentation remains an underutilized safeguard. The evidentiary weight of contemporaneous, granular, and syntactically precise narrative entries in electronic health records constitutes a robust affirmative defense against negligence claims. One must therefore prioritize lexical specificity over checkbox compliance.

Gabriella Jayne Bosticco

November 28, 2025

My husband’s a GP in Texas. He started doing the detailed notes after his buddy got sued. Now he has a template in his EHR. He even asks patients, ‘Have you ever switched this med before? Did anything weird happen?’ It turns the conversation into a partnership. And honestly? Patients feel safer. So do I.

Sarah Frey

November 30, 2025

Thank you for writing this. It’s easy to feel isolated in this struggle. But the truth is, many of us are quietly doing the right thing-documenting, advocating, and choosing safety over convenience. You’re not alone. And your diligence matters more than you know.