Chronic heartburn isn’t just annoying-it’s a warning sign. If you’ve had acid reflux for more than five years, especially if it happens several times a week, your esophagus may be changing in ways you can’t see. That change is called Barrett’s esophagus, and it’s the body’s attempt to heal itself from years of acid damage. But this healing comes with a dangerous twist: it increases your risk of esophageal cancer.

What Exactly Is Barrett’s Esophagus?

Barrett’s esophagus happens when the normal tissue lining your esophagus-soft, pink, and made of squamous cells-gets replaced by a different kind of tissue. This new tissue looks more like the lining of your intestines. It’s called intestinal metaplasia, and it’s the official diagnostic marker. This switch doesn’t happen overnight. It takes at least 10 years of constant acid exposure from GERD to trigger it.Barrett’s esophagus doesn’t cause new symptoms. You won’t suddenly feel different. If you have it, you probably just think your heartburn is getting worse. That’s the problem. People ignore it. They pop antacids, avoid spicy food, and assume they’re fine. But behind the scenes, the cells in your esophagus are slowly turning into something that can become cancer.

Who’s at Risk?

Not everyone with GERD gets Barrett’s esophagus. But certain people are far more likely to develop it.- Men are three times more likely than women to develop it.

- White men over 50 with long-term GERD have the highest risk.

- Obesity, especially belly fat, increases pressure on the stomach and pushes acid upward.

- Smoking doubles the risk.

- If you’ve had heartburn more than three times a week for over 20 years, your chance of developing Barrett’s is 40 times higher than someone without chronic reflux.

Even if you don’t fit all these boxes, if you’ve had daily acid reflux for over a decade, you should talk to a doctor. The numbers don’t lie: about 5.6% of the U.S. population has Barrett’s esophagus. Among people with chronic GERD, that number jumps to 10-15%.

How Is It Diagnosed?

You can’t diagnose Barrett’s esophagus with a blood test or an X-ray. The only way to know for sure is through an upper endoscopy.During the procedure, a thin, flexible tube with a camera goes down your throat. The doctor looks for areas of salmon-colored tissue-unlike the normal pale lining-rising up from where your esophagus meets your stomach. But seeing it isn’t enough. Biopsies are required.

The standard method is the Seattle protocol: four tissue samples are taken every 1 to 2 centimeters along the abnormal area. That’s usually 12 to 24 samples total. Why so many? Because cancer starts in tiny patches. One missed spot could mean missing early signs of dysplasia.

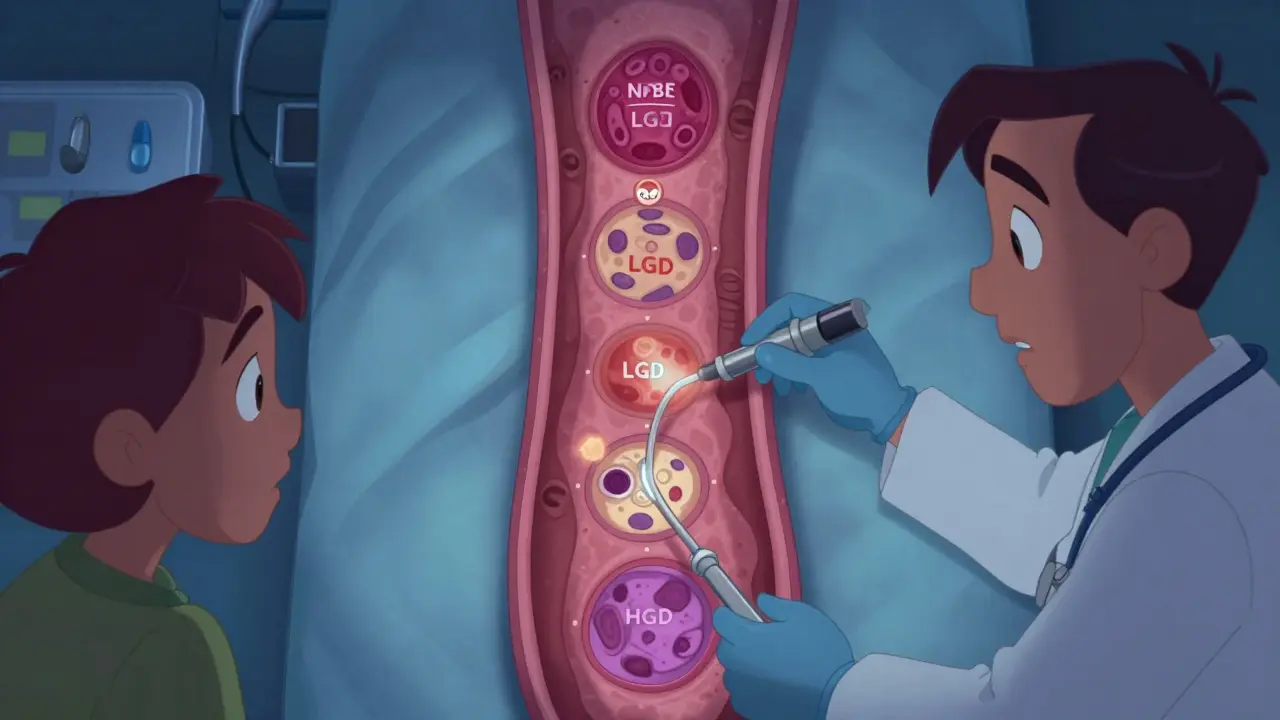

The results are classified into four levels:

- Non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (NDBE)-no precancerous changes.

- Indefinite for dysplasia-unclear if changes are real or just inflammation.

- Low-grade dysplasia (LGD)-early signs of abnormal cell growth.

- High-grade dysplasia (HGD)-severe changes that are very close to cancer.

High-grade dysplasia carries a 6-19% chance of turning into cancer each year. That’s not a small risk. It’s a red flag.

Screening Guidelines: Who Should Get Tested?

There’s no universal screening for everyone with heartburn. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends endoscopic screening only for people who meet specific criteria:- Men with chronic GERD (lasting more than 5 years)

- Who have symptoms at least once a week

- And have at least one extra risk factor: age over 50, White race, obesity, or smoking history

Women and men without these risk factors generally aren’t screened. Why? Because the risk is low, and endoscopies are expensive. Screening everyone would cost the U.S. over $1.2 billion a year-and most people screened would never develop cancer.

But here’s the catch: many people don’t know they’re at risk. A study from the Esophageal Cancer Action Network found that 68% of Barrett’s patients had symptoms for over five years before being diagnosed. They thought their heartburn was normal. It wasn’t.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

If you’re diagnosed with non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, you’re not in immediate danger. But you need monitoring. The standard is a repeat endoscopy every 3 to 5 years.If low-grade dysplasia is found, it’s usually confirmed by a second pathologist. Then, surveillance is shortened to every 6 to 12 months. Some doctors now recommend treatment even at this stage, especially if you’re young and healthy.

High-grade dysplasia is treated-not monitored. The goal is to remove or destroy the abnormal tissue before it becomes cancer. The most common method is radiofrequency ablation (RFA). It uses heat to burn off the damaged lining. Studies show RFA clears dysplasia in 90-98% of cases. Cryotherapy, which freezes the tissue, is another option.

One patient from Mayo Clinic described how RFA wiped out his high-grade dysplasia in six months. He didn’t need surgery. He didn’t lose his esophagus. He just needed the right treatment at the right time.

Can You Prevent It From Getting Worse?

Yes-but not just by taking PPIs. Proton pump inhibitors like omeprazole help reduce acid and relieve symptoms. But here’s the truth: many people on PPIs still have acid refluxing into their esophagus. Studies using pH monitors show that even with daily PPI use, up to 45% of patients aren’t fully protected.Real protection means total acid suppression. That means:

- Taking high-dose PPIs (like 40 mg of omeprazole twice daily) if recommended

- Not eating within 3 hours of bedtime

- Elevating the head of your bed by 6 to 8 inches

- Losing weight if your BMI is over 25

- Avoiding chocolate, caffeine, alcohol, fatty foods, and spicy meals

- Quitting smoking

These aren’t suggestions. They’re medical necessities if you have Barrett’s esophagus. Medication alone won’t cut it. Your lifestyle has to change.

What’s New in Testing and Treatment?

The field is moving fast. In 2021, Medicare started covering a blood test called the TissueCypher Barrett’s Esophagus Assay. It analyzes molecular markers in biopsy samples to predict cancer risk with 96% accuracy. It’s not a replacement for endoscopy-but it can help decide who needs frequent monitoring and who can safely wait longer.A $2.4 million study running from 2023 to 2026 is testing DNA methylation markers to cut down unnecessary endoscopies by 40%. That’s huge. Right now, 95% of people with Barrett’s esophagus will never get cancer. But they all get endoscopies anyway. That’s a lot of procedures, anxiety, and cost.

And guidelines are evolving. In 2022, the American Gastroenterological Association updated its rules to recommend treatment for all patients with confirmed low-grade dysplasia-not just those with high-grade. The AIMS-2 trial showed 94% of LGD cases stayed gone after five years with ablation.

Why This Matters

Esophageal adenocarcinoma is deadly. Only about 20% of people survive five years after diagnosis. That’s worse than many other cancers. But here’s the good news: if caught early-before it becomes cancer-Barrett’s esophagus can be reversed. RFA and cryotherapy can restore normal tissue. You can live a normal life.The problem isn’t the treatment. It’s the delay. People wait. They think, “It’s just heartburn.” But chronic GERD isn’t just heartburn. It’s a silent, slow-burning fire in your esophagus. And Barrett’s esophagus is the smoke.

If you’ve had daily acid reflux for over 10 years, especially if you’re a man over 50, overweight, or a smoker, talk to your doctor. Don’t wait for pain. Don’t wait for swallowing trouble. Get screened. It’s a simple procedure that could save your life.

What If I’m Not in the Screening Group?

Even if you don’t meet the official criteria, pay attention to your body. If your heartburn is getting worse, or you’ve started having trouble swallowing, regurgitating food at night, or feeling chest pain that isn’t heart-related-see a gastroenterologist. Don’t assume it’s just aging or stress.Many people with Barrett’s esophagus didn’t fit the profile. They were women. They were younger. They didn’t smoke. But they had long-term reflux. And they paid the price because no one thought to check.

Knowledge is power. If you know you have chronic GERD, you have a responsibility-not just to yourself, but to your future health. Don’t ignore the signs. Don’t normalize the pain. Ask for an endoscopy. It’s not scary. It’s life-saving.

Final Thoughts

Barrett’s esophagus is not a death sentence. It’s a warning. And like any warning, it’s only dangerous if you ignore it. The tools to detect and treat it exist. The science is solid. The treatments work.The real challenge isn’t medical. It’s awareness. People don’t know they’re at risk. Doctors don’t always ask the right questions. And patients don’t push back.

Be the one who does. If you’ve had GERD for more than five years, especially with other risk factors, get tested. It’s not about fear. It’s about control. You can’t stop the past-but you can stop what comes next.

Peyton Feuer

January 4, 2026

man i had heartburn for like 12 years and never thought twice about it till my buddy got diagnosed with barrett’s and lost his esophagus. i went in for an endo last year and turns out i had non-dysplastic barrett’s. doc told me to drop the pizza and start sleeping upright. best decision i ever made. still take my ppi but now i also avoid coffee after 3pm. no more midnight snacks. life’s better now.

Angie Rehe

January 5, 2026

the american college of gastroenterology’s screening guidelines are a joke. they’re not protecting people-they’re protecting insurance companies. 68% of barrett’s patients had symptoms for over five years before diagnosis? that’s malpractice. if you’re a white male over 50 with reflux, you’re a walking cancer risk. why aren’t we doing population-wide screening? because it’s cheaper to wait until they’re stage 4. this isn’t medicine-it’s profit-driven triage.

Siobhan Goggin

January 6, 2026

thank you for writing this. i’ve been managing reflux for over 15 years and never realized how much of a silent threat it was. i started elevating my bed and cutting out chocolate after reading this. it’s not glamorous, but i feel more in control. small changes matter. you’re not alone in this.

Shanna Sung

January 7, 2026

barrett’s is a scam. the whole thing is pushed by big pharma and endoscopy centers. they want you scared so you’ll keep buying ppi’s and getting scoped every 3 years. the real cause? glyphosate in your food. the esophagus is just reacting to poison. they don’t tell you that because the cdc gets funding from Monsanto. ask yourself-why does no one talk about the herbicide connection? because they’re paid to stay quiet.

mark etang

January 8, 2026

it is imperative to underscore the clinical significance of early detection in the context of esophageal adenocarcinoma. the data supporting endoscopic surveillance and radiofrequency ablation are robust, reproducible, and validated across multiple prospective cohorts. adherence to the seattle protocol and timely intervention in cases of high-grade dysplasia demonstrably improve survival metrics. i urge all individuals with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease to engage in proactive, evidence-based healthcare decisions.

josh plum

January 8, 2026

you people are so naive. ppi’s don’t fix anything-they just mask it. the real issue? your gut is dying from processed food and sugar. barrett’s isn’t from acid-it’s from your body screaming because you’ve been poisoning it for decades. and don’t get me started on how the medical system ignores the microbiome. you think a camera down your throat fixes that? nope. you need probiotics, fasting, and to stop eating like a zombie. but hey, keep popping pills and paying $2000 for an endo. that’s the american way.

John Ross

January 10, 2026

in japan, they screen everyone over 40 with chronic reflux. no risk stratification. no cost-benefit analysis. they just do it. and their esophageal cancer rates are 70% lower than ours. why? because they treat the esophagus like it matters. here, we wait until you’re coughing up blood before we care. this isn’t about risk factors-it’s about cultural priorities. we value convenience over longevity. and that’s a tragedy. the technology exists. the will doesn’t.

Clint Moser

January 11, 2026

they say barrett’s is from acid but what if it’s the ppi’s themselves? studies show long-term ppi use changes gastric pH and lets bad bacteria grow. maybe the acid isn’t the enemy-the treatment is. and the biopsies? they’re misreading inflammation as dysplasia. i’ve seen it. my cousin got diagnosed with lgd then went to a second doc and they said it was just healing. they’re overdiagnosing to push ablation. it’s all profit. and the dna methylation test? that’s just another way to make you pay more. don’t trust the system.